Well you should see my story-reading baby

You should hear the things that she says

She says “Hon, drop dead, I’d rather go to bed

With Gabriel García Márquez

Cuddle up with William S. Burroughs

Leave on the light for bell hooks

I’ve been flirtin’ with Pierre Burton

‘Cause he’s so smart in his books”

—Moxy Früvous, “My Baby Loves A Bunch Of Authors”

I love Alison Bechdel’s Dykes To Watch Out For, and have from the day I came out and picked up my first GO-Info (strip # 140, “The Last Tango”, where Mo and Harriet have sex one last time before breaking up for good). Until it ended earlier this year, it was the first thing I read when picking up Xtra! West, and I could always count on it to make me laugh, make me think, or both. I own all the collected books, including The Indelible Alison Bechdel.

But, there was one book of hers missing from my collection: a non-DTWOF book I didn’t even know existed until this summer, when I saw it as part of an exhibition on animation and comics at the Art Gallery. I read it all the way through in one sitting, absolutely captivated. It’s poignant, disturbing in parts, brutally honest, yet at the same time masterfully intellectual and literate. A couple of weeks ago I bought it as a Christmas present to myself, and I’ve been compulsively rereading it over and over again. I guess this post is a way to get it out of my head.

In brief, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic is the story of Bechdel’s growing up, and her complicated relationship with her father. A few weeks after coming out to her parents at age 19, she learned he was gay. A few months later he was dead, possibly having committed suicide. Fun Home is Bechdel’s attempt to work out the threads of his life, her own life, and how the two intersected.

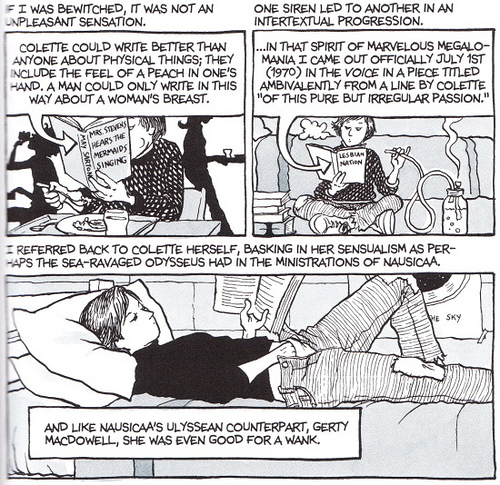

But Fun Home is more than a memoir. It’s a story about stories: specifically, the books that Alison and her father both loved—and for the last couple of years of his life, the only way they related to each other. Fun Home is peppered with allusions and quotes from F. Scott Fitzgerald, Albert Camus, Marcel Proust, James Joyce, Oscar Wilde, Colette and Greek mythology, among many others, but they never (well, hardly ever) feel forced. Without bogging things down in tedious literary analysis, they provide just enough insight to not only enrich the story but get me excited about reading the originals as well.

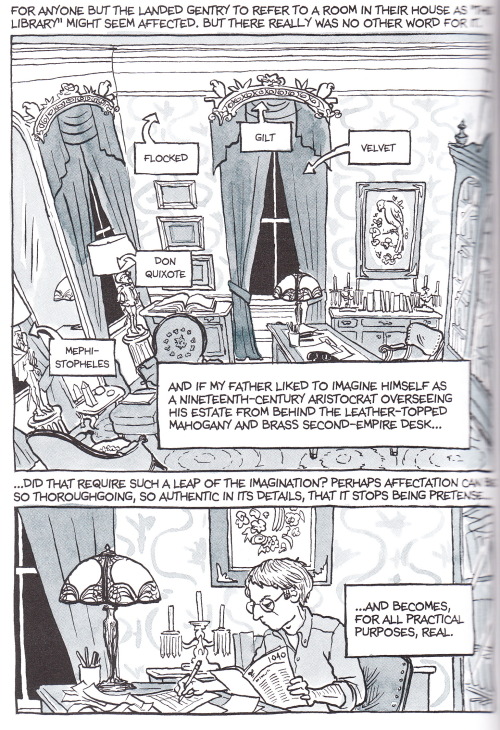

Alison (I feel a bit awkward referring to her by her first name, but what can you do?) found her taste for The Classics in grade 12, but before that, her relationship with her father was mostly distant, even hostile at times. Bruce Bechdel, it seems, was not an easy man to live with. A remote, authoritarian father and husband, prone to bouts of rage, he spent much of his spare time reading or restoring his family’s 19th century home. He was obsessed with beauty, but it was a narrow, oppressive kind of beauty, shallow and fragile, with no room for other people’s needs or tastes. The home he recreated was an artfully arranged, jumbo-sized closet, as much a museum as a place to live.

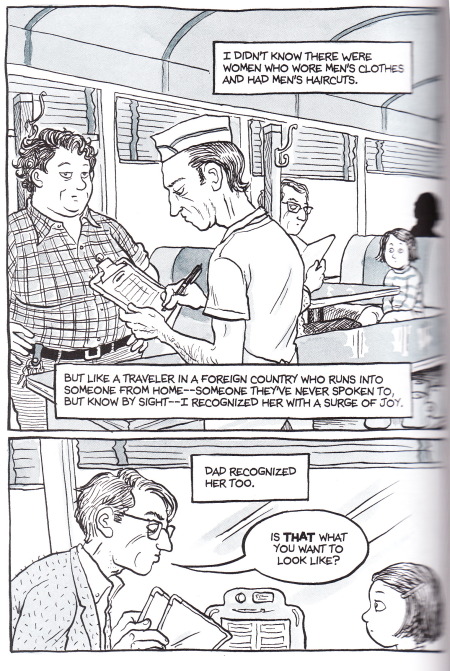

Everything in Bruce Bechdel’s world had to be just so, and that included his only daughter Alison. They were polar opposites in many ways, butch girl and sissy man; him trying to dress her up into a perfect model of femininity, her resisting his efforts as best she could. His intent is ambiguous: it’s not clear if she was just another canvas on which to work his art, or if he was actually trying to quash her budding queerness.

“Is that what you want to look like?” There are so many things wrong with that question. Is looking butch a worse sin than queerness? Would it have been better for her to look pretty, marry and have affairs with high school students on the sly?

Closeted father aside, there’s a lot I can relate to in Alison’s story. Both my parents are teachers as well (retired now) and have never been very demonstrative either. Like Alison, I realised I was gay before I had sex. And again like her, I bought a truckload of books upon coming out—biographies, histories, politics, humour, psychology, anything really, I wasn’t too choosy back then.

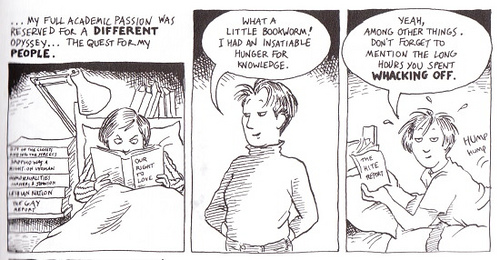

And actually, that part was familiar. The Indelible Alison Bechdel reprinted her coming-out story; originally published in 1993, it focused on the immediate circumstances surrounding her revelation, making contact with the local gay community, and ending with her first time with another woman. But in the meantime bookish, intellectual Alison had plowed through many, many books in an attempt to find, and understand, her new community. The masturbation scene above was played for giggles in 1993 but turned into something more serious in 2006, almost transcendent, a necessary step in her journey. Only the “good for a wank” brought it down to earth a bit.

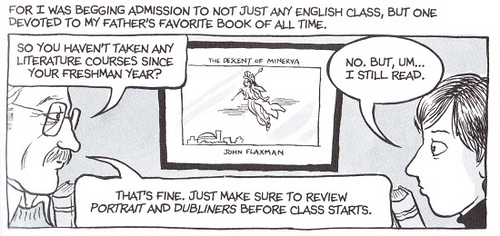

Okay, I promised myself I wouldn’t be doing any high-falutin’ literary analysis (“Marlow’s steamer? penis. The Congo? vagina” Hee) but there are a few details that jumped out at me. Consider the picture on her professor’s office wall. It so happens (thank you Wikipedia!) that “The Descent of Minerva to Ithaca” is one of a series of engravings John Flaxman did to illustrate the Odyssey. Guess which book was studied in this English class? That’s right: Joyce’s Ulysses.

There’s more, though. This meeting took place the exact same day Alison realised she was a lesbian. And in the 1993 version of her coming-out story, she compares her revelation to the birth of Athena. “You know the story. She springs, fully grown and in complete armor, from Zeus’s head.”

Was that picture really there in her professor’s office? I don’t think it matters much. In a few instances, Alison points out a stray detail and insists it was in fact real. This still leaves many unaccounted for, but that’s fine. In a memoir, factual accuracy may sometimes take a back seat. I’ll trust that the story is true enough, and move on.

So there you have it. Honestly, going through Fun Home again and again has left me exhausted, but in a good way. I grieve for a man who died before he ever had the chance to truly live, but celebrate the life of a woman who escaped his labyrinth and created something truly beautiful. And maybe, one of these days, I’ll feel brave enough to tackle Proust.